Stranger than fiction: when prestige TV needs a perfect circle, it calls a robot

On the set of Stranger Things 5, AGITO solved a very specific problem — and quietly revealed how high-end television now works.

Stranger Things, Netflix’s flagship exercise in supernatural nostalgia, had taken over an entire studio lot for its fifth and final season. Twenty-plus soundstages. Backlots dressed to within an inch of their lives. Props so detailed they blinked. Creatures from the Upside Down lay strewn across the floor with the casual inevitability of a long-running hit.

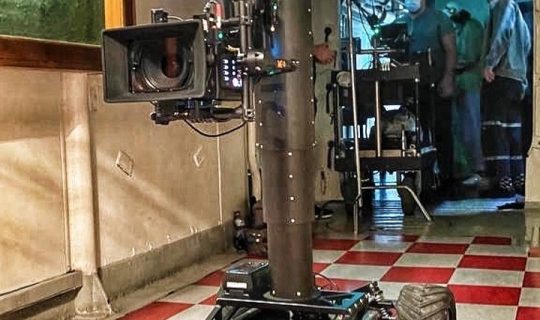

And somewhere amid this very deliberate chaos, a small robotic camera dolly was being driven around between setups, largely to show off what it could do. This was AGITO. It did not arrive with fanfare, nor with a laminated badge announcing its importance; it was there as a demo — the kind of equipment that finds its way onto set not because it has been formally requested, but because someone, exercising quiet foresight, thought it might come in handy.

That someone was Max DeRoin, who runs Cinertia Systems [a company championing AGITO within film, TV and live broadcast] alongside co-founder Alex Slupski. Cinertia had been brought onto the production by CineMoves, who were supplying specialist rigs for the show’s grip work and needed Cinertia’s drones, operated by Alex. Max, meanwhile, was on set with AGITO to showcase it — driving it between stages, letting it stretch its legs, more out of professional curiosity than any expectation it would be called upon to earn its keep.

But as often happens on large sets, someone noticed. In this case, it was the show’s Best Boy, a role that has always combined deep technical knowledge with a finely tuned radar for unfamiliar kit. “He saw it and asked what it was,” Max says. “So, we talked about it. What it could do. How it moved.”

Not long after, a familiar problem surfaced.

Letting the Performance Breathe

The shot itself was modest in description and unforgiving in execution.The camera needed to orbit Kali, the series’ telekinetic outlier, strapped upright to a piece of scientific equipment. The movement had to be exact: no drift, no inconsistency, no human push introducing microscopic errors that would only reveal themselves later in post. Because any deviation wouldn’t just be noticeable; it would complicate the visual effects work downstream — and on a schedule already stretched thin, there was little appetite for discovering those problems after the fact.

The orbit wasn’t about showing off – it was designed to trap the character in place, visually reinforcing her lack of control.

Traditional dollies were quickly ruled out. A Fisher, pushed by hand, would never be repeatable enough; cranes and tracking vehicles were either too large or too imprecise for the space; and while drones had already earned their place elsewhere in the production, this was not a moment for flight. What the production needed was a fully self-propelled robotic camera dolly – something that could move in isolation, hold its path, and repeat the move exactly.

“They needed something that could just do the same thing every time,” explains Max. “They needed AGITO.”

Speed became another variable to be handled with discipline rather than flair: slow passes, faster ones, subtle changes in pace, easing in and out as required. Crucially, with AGITO every variation could be repeated precisely — the rhythm of the movement adjusted and then locked in.

Old Track, New Tricks

In a small irony that will delight grip departments everywhere, the flashy-looking robot ran on distinctly unglamorous foundations. Due to availability constraints, the team sourced a limited supply of ageing Cobra dolly track – more than 30 years old – that happened to be the right width.

AGITO ran on track not out of necessity, but practicality. The floor in that part of the set wasn’t perfectly level, and the production wanted to keep the camera configuration simple. That meant no stabilised remote head, no elaborate rigging and no additional layers of complexity that might, at the wrong moment, develop opinions. Instead, the camera sat on a Cartoni fluid head, which, once locked off, stayed put.

“It was actually my first time ever putting a fluid head on AGITO,” Max admits. “But it worked perfectly; AGITO handled the movement, rotating cleanly through the shot, take after take.”

There is something subtly reassuring about that sentence. Not “worked eventually.” Not “worked after a workaround.” Just: worked perfectly.

AGITO was only on set for a handful of days. It wasn’t wheeled out for every setup. It didn’t replace cranes, drones or traditional dollies. It arrived, solved a very specific problem, and left again. Which is, in many ways, the point.

In an industry increasingly fond of grandeur, not just on screen but behind the scenes, the system’s success lies in its restraint. When it works properly, no one notices it at all. The movement feels calm, deliberate, inevitable. “The best version of it,” Max says, “is when no one’s really talking about it afterwards. The audience doesn’t think about robotics. They think about the scene.”

Everyone Agrees Not to Mention the Robot

For years, robotic camera systems have been fixtures of live broadcast productions, where repeatability and efficiency are a must. High-end drama has been slower to embrace them, favouring established workflows and familiar tools – partly out of tradition, partly because film crews are artisans, and partly because nobody wants to be the person who suggested a robot and then have it fail in front of everyone. But that reluctance is beginning to soften.

Prestige television now operates on cinematic scales and cinematic schedules; sets are denser, shots are more ambitious, and productions are increasingly willing to adopt tools that deliver precision without adding complexity – because the real enemy is not technology; it’s time.

AGITO’s appearance on Stranger Things 5 wasn’t about replacing traditional craft. It was about extending it; adding a quiet, reliable option for moments when human hands, however, skilled, weren’t the best solution.

And so, somewhere in the final season, amid Demogorgons and carefully dressed destruction, there is a shot that moves in a perfect circle around Number Eight, drawing in the viewer without ever calling attention to how it was achieved. No one watching at home will wonder what made that movement possible. They won’t think about robotics, track widths or locked-off fluid heads. They’ll simply feel the moment land – which, on a set that size, is about as close to perfection as anyone can ask for.